Patients' attitude towards coercion and violence in providing stationary psychiatric aid: ethical and preventive aspects

Abstract

Background: People with mental disorders are most vulnerable in respect to their rights and legitimate interests wile obtaining psychiatric aid. The aim of the study: To develop recommendations for improving the conditions of stay and treatment of persons with mental disorders in psychiatric clinics based on the study of the frequency and forms of coercion and violence applied to patients, and their personal assessment. Materials and methods: Using the medico-sociological method and the modified Bogardus social distance scale, 271 patients were examined in 3 regional psychiatric hospitals: 110 men and 161 women. Results: Patients of psychiatric clinics are socially maladapted, uncritical to their disease. They prefer not to have close relationships with people with mental disorders. Women are often subjected to coercion and violence in a psychiatric clinic. Patients justify coercion in treatment by psychiatrists. The use of physical restraint is considered the prerogative of junior medical staff, but the personal participation of a psychiatrist or the involvement of other patients in cases of threat to others is allowed. A quarter of patients speak out against the use of coercion in the hospital. Compulsory treatment of persons with mental disorders is justified by most patients if their well-being or public safety is in danger. The hospital considers it necessary to control drug treatment and force-feeding when patients refuse to eat. Most patients are not completely satisfied or indifferent to the conditions of living and treatment in the clinic. Conclusion: Creating a comfortable environment in psychiatric clinics requires the development of standards for equipping the wards and premises of the department. Minimization of the use of physical restraint and coercion requires clinical and legal regulation of their use, training of medical personnel in medical bioethics, education of patients and their families.

Introduction. An increase in the level of education and awareness stimulates the psychiatric patients’ expectations towards the respect of their rights and the quality of treatment provided [1]. At the same time, persons with mental disorders are most vulnerable in terms of their rights and legitimate interests in the provision of psychiatric care [2]. Often, the hospitalization process itself is accompanied by violations of the rights of persons with mental disorders, such as the right to be informed about medical documents, to actively participate in the formation of a treatment plan, to refuse treatment or to be immediately discharged at any stage of therapy [3].

In involuntary hospitalization, rights and freedoms are restricted [4]. Often, in the first days and weeks of hospitalization in a psychiatric clinic, restrictive measures are applied to patients in the form of placement in a ward with a 24-hour medical post [5, 6]. Therefore, most people with mental disorders negatively perceive involuntary hospitalization and consider it inadmissible for medical staff to use measures of isolation, physical restraint, forced injection and feeding [7].

During a stay in a psychiatric ward in case of behavioral disorders and heteroaggression with a life threat to others, the psychiatrist prescribes physical restraint and isolation [8]. However, there are often cases of abuse of restrictive measures and the use of physical restraint and isolation by orderlies and nurses without a psychiatrist's appointment [9]. Rude attitude towards people with mental disorders, intimidation, unjustified use of physical force, compulsion to perform various tasks in the department are reported [10]. At the same time, patients often do not have the opportunity to contact the administration in case of violation of their rights, and the responses to complaints are perfunctory [11].

Coercion and violation of patients’ rights during hospitalization leads to a decrease in compliance up to a complete refusal of medical care, which increases the risk of exacerbation of psychopathological symptoms and re-hospitalization [12]. The use of restrictive measures in the provision of psychiatric aid poses medical and legal problems and needs to be clearly regulated, including ways of social and legal protection, both for patients and staff of psychiatric clinics [13, 14].

The aim of the study was to study the attitude of patients towards coercion and violence in a psychiatric hospital in order to develop recommendations for improving the conditions of stay and treatment of persons with mental disorders in a psychiatric hospital.

Materials and methods. The study was conducted in 2018 through an anonymous and voluntary questionnaire survey of 271 patients aged 15 years and older in acute psychiatric wards of state psychiatric hospitals in 3 subjects of the Russian Federation: Belgorod, Volgograd and Voronezh regions. The group of respondents included persons suffering from chronic mental disorders (according to ICD-10): Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders (F00-F09), Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F20-F29), Mood [affective] disorders (F30 -F39), characterized by mild to moderate severity of psychopathological symptoms. All the patients gave documented consent to the study procedure. Patients’ anonymity is preserved.

Our study had some limitations. The survey was carried out only among patients of acute psychiatric departments, while patients of the departments of neurotic disorders and outpatients did not participate in the survey. The respondents participated in our study at the stage of the formation of persistent drug remission, which excluded the possibility of influencing the opinion of acute psychotic symptoms and was accompanied by a partial restoration of critical abilities, and, possibly, more socially acceptable answers to the questionnaire. In this regard, the prevalence of coercion and violence in the present study was not studied as a ubiquitous phenomenon in psychiatry, requiring more respondents and covering all types of mental health care. At the same time, this cohort of patients is more likely to encounter restrictive measures, so the results of the study can be extrapolated to the entire mental health service.

The subjects were divided into 2 groups according to gender: the male group included 110 patients aged 19-76 (42.3±11.5) years, the female group included 161 patients aged 15-80 (41.8±13.4) years old. Patients' attitudes towards coercion and violence in the provision of inpatient psychiatric care were studied using the medico-sociological method: the author's questionnaire and the modified Bogardus social distance scale [15].

The questionnaire consisted of 32 questions related to socio-demographic information, assessment of person’s own state of mental health, opinions on the application of restrictive measures and coercion during treatment in a psychiatric clinic, the comfort of staying in a psychiatric clinic, and the effect of coercion and violence factors on adherence to treatment.

Bogradus social distance scale was interpreted in two ways. The average score (mean) was calculated and the social distance of the group of respondents in relation to persons with mental disorders was determined. The ranking of social distance included 5 options: close relationships (points 1-2), open relationships (points 3-4), distancing (point 5), isolation (point 6), rejection (point 7).

The database was processed using nonparametric statistic methods (descriptive statistics, c2 criterion with Yates correction for 2x2 contingency tables, odds ratio) using the Statistica 6.0 statistical software application.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Institute of Belgorod State National Research University and complies with the provisions of the 1995 Helsinki Declaration, as amended and supplemented (Edinburgh, 2000) – protocol No. 12 dated February 6, 2018.

Results and discussion. The clinical structure of the patients was as follows: Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F 20-29) – 212 (78.2%) people; Affective mood disorders (F 30-39) – 31 (11.4%) people; Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders (F 00-09) – 28 (10.4%) people. Affective disorders were more common (c2=5.5897 p=0.019; OR=3.2% CI=1.2-9.0) among women (15.6%) than among men (5.5%). Organic mental disorders were statistically significantly more often (c2=13.7825 p=0.000) in male patients (19.1%) than in female patients (4.3%).

The majority of patients (male and female) - 207 (76.4%) people - did not have their own family for the period of the study. Among friends and acquaintances in 49 (44.5%) men and 78 (48.4%) women there were persons with mental disorders who sought medical help from psychiatrists. The study of social status showed that a total of 137 (50.5%) patients had a disability due to a mental disorder, predominantly 2 groups (pronounced and persistent mental disorders that impede social functioning). Of the remaining 134 (49.5%) patients, more than half were unemployed for the study period – 82 people. The rest worked in unskilled jobs. No gender differences in social status have been identified.

Our results are consistent with previous studies [16], which showed that the majority of patients in a psychiatric hospital do not have their own families, are disabled due to a mental disorder, or are unemployed, indicating a low level of their social and work adaptation. They do not have a critical attitude towards their health and the severity of their mental disorder; only the presence of psychological problems or mild mental disorders is recognized.

A study of patients’ personal assessment of their mental health (Table 1) revealed a pronounced non-critical attitude in the majority of the examined. Thus, 26.4% of males and 21.7% of females completely denied the fact that they had mental disorders. The presence of psychological level problems was recognized by 51.8% of males and 37.6% of females (the differences are not statistically significant). The presence of a mild mental disorder was seen only by 16.6% of the examined. Relatively, only 10.3% of patients (without gender differences) were critical of their state of health. Thus, the vast majority of patients in acute psychosis departments are uncritical towards their mental disorder.

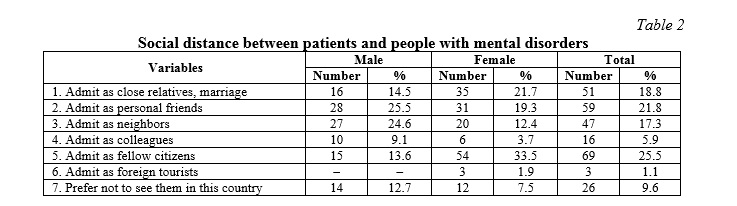

Verification of the relationship (the Bogardus social distance scale) of the respondents to persons with mental disorders (Table 2) showed that 14.5% of men and 21.7% of women admit them as close relatives or spouses and 25.5% and 19.3%, respectively, admit them as friends. A quarter (24.5%) of male patients were more loyal than female (9.1%) in terms of accepting people with mental disorders as neighbors (c2=5.881 p=0.002 OR=2.3% CI=1.2-4.7).

The attitude of females with mental disorders to mentally sick people is more closed and distant (c2=12.6135 p=0.001 OR=3.2 95%CI=1.6-6.4) than among men. Whereas 33.5% of female respondents only accept mentally sick people as citizens of their country, only 13.6% of male respondents show similar attitude. The odds ratio indicates that the number of patients who are hostile to mentally sick people is 3 times higher among women than among men. Moreover, 9.6% of respondents experience a pronounced alienation and hostility towards people suffering from mental disorders, and would not want to see them in the country even as tourists.

Analysis of the mean score on the modified Bogardus scale showed the absence of gender differences in social distance. Patients prefer to allow persons with mental disorders for a distance slightly further than “street neighbors”. The average M±d score was 3.4±1.9 for women and 3.3±1.9 for men.

When using the modified Bogardus social distance scale, it was revealed that close relationships (friendly, family, intimate) with people suffering from mental disorders were admitted by 40.6% of respondents (no gender differences were found). Men preferred open relationships (formal social contacts, communication at work) more often (33.7%) than women (16.2%): c2=10.242, p=0.002, OR=2.6 95%CI=1.4-4.9. 33.5% of the interviewed female patients preferred to distance themselves from mentally ill patients, minimizing the need to communicate with them, statistically significantly more often (c2= 12.6135 p=0.001) than male (13.6%), odds ratio OR=3.2 95%CI=1.6-6.4. Among all survey participants, 1.9% of women admitted the social isolation of people suffering from mental disorders, considering only remote visual contacts acceptable without any communication. Among the respondents, 12.7% of men and 7.5% of women completely denied for themselves the possibility of contacts with the mentally sick people, rejecting them as members of society.

According to our data, patients in psychiatric hospitals prefer to have a social distance with persons with mental disorders, somewhat more distant than neighbors on the street, which correlates with the results of previous studies [17]. The current study found that less than 50% of patients tolerate close relationships with persons with mental disorders. We have identified gender differences: men more often prefer open relationships and social contacts, while women prefer to distance themselves from this category of persons or their complete social isolation. Social distancing, in our opinion, is associated with a high level of stigma and self-stigmatization, based on negative attitudes towards persons with mental disorders in society, which is consistent with the studies of Modi et al. [18].

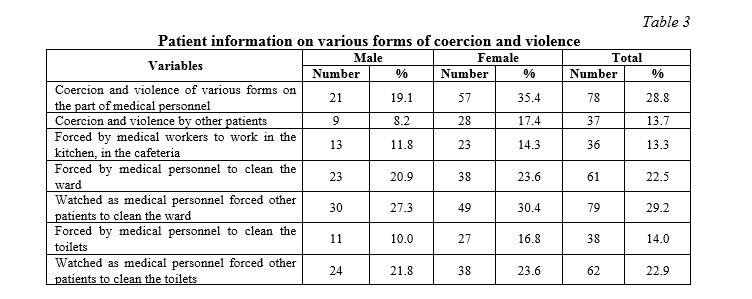

Various types of coercion and violence by medical workers were noted by 35.4% of women (c2=7.7072 p=0.006; OR=2.3 95%CI=1.3-4.3) and 19.1% of men. 17.4% of women (c2=3.9533 p=0.047 OR=2.4 95%CI=1.0-5.7) and 8.2% of men suffered coercion and violence from other patients. Thus, contrary to expectations, violence and coercion both on the part of medical workers and other patients were more often experienced by female persons. A total of 13.3% of patients of both genders noted that during the period of inpatient treatment they were involved in work in the kitchen and in the cafeteria, 22.5% were involved in wet cleaning their wards and corridors, and 14.0% were involved in cleaning the toilet rooms (Table 3).

As more accustomed to the mundane housework, a greater number (c2=5.3461 p=0.021 OR=1.8 95%CI=1.1-3.1) of females (64% vs. 49.1% of males) considered it acceptable for patients, especially with long bedding periods, to participate in cleaning the wards. Male patients (50%) reported their unwillingness to participate in cleaning the hospital territory, statistically significantly more often (c2=4.2502 p=0.004) than female patients (36.6%), with a predictive probability of almost twice as often (OR=1.7% CI=1.0-2.9).

Patients in psychiatric hospitals experience various forms of coercion and violence by the medical staff [19,20]. Our results are consistent with studies carried out in this area, while it was found that women more often than men indicate coercion and violence experienced in a psychiatric hospital by medical staff, aggression from other patients. Staniszewska et al. [21] note that patients in psychiatric wards perform cleaning and technical work; in the present study, about 30.0% of patients of both sexes indicated this type of compulsion. We have established gender differences: women who are accustomed to housework are more likely to express an opinion about the admissibility of patients' participation in cleaning the premises.

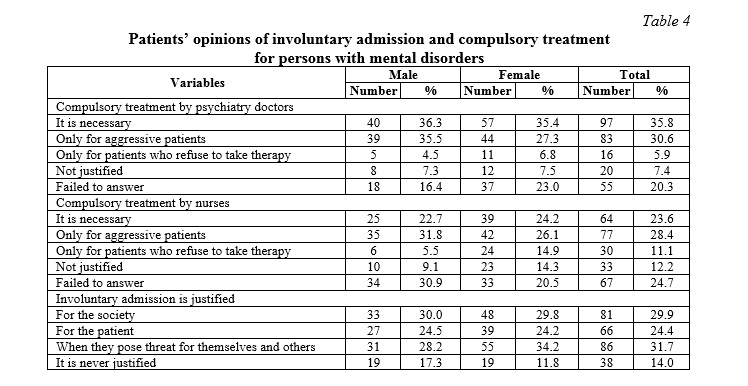

A study of the patients’ point of view on compulsory treatment of persons suffering from mental disorders by psychiatry doctors (Table 4) showed that 36.3% of males and 35.4% of females considered it justified. Another 30.6% of patients of both genders considered compulsory treatment justified only in cases of aggressive behavior. Refusal of therapy may be the reason for compulsory treatment by a psychiatrist according to 4.5% men and 6.8% women. In total, only 7.4% of patients of both genders reported inadmissibility of compulsory treatment under any circumstances. Every fifth patient (20.3%) failed to answer this question. Thus, despite the fact that only 10.3% of patients admit that they have a serious mental disorder, the vast majority actually agree with the necessity of compulsory treatment.

Few studies have investigated the prevalence of coercion [22] and patient attitudes towards it [23]. The present study showed that the majority of patients are in favor of coercion of treatment by psychiatrists, which is consistent with the data of Lawrence et al. [24]. At the same time, some authors consider insufficient criticism of their mental health as a risk factor for negative attitudes towards coercion [25]. Our point of view on the connection with the dominant paternalistic model of providing mental health care and the imposition of increased responsibility of psychiatrists not only on the state of health of patients, but also for their asocial, antisocial and criminal behavior, correlates with previous studies [24]. We identified gender differences: females admit the possibility of coercion to treatment by nurses more often than males.

Compulsory treatment of persons with mental disorders by nurses is justified in all cases by 23.6% of patients of both genders. Another 28.4% allow coercion only if the patient is aggressive. Refusal of treatment as a sufficient reason for coercion on the part of nurses is considered acceptable by female patients more often (14.9%; c2=5.01 p=0.003 OR=3.0 95%CI=1.1-8.6) than by male patients (5.5%). The majority of patients, 82.7% of males and 80.2% of females, vote for compulsory treatment of persons suffering from severe mental disorders, which should ensure safety for the society, well-being and safety for the patients themselves. Only 14.0% of patients consider compulsory treatment of persons with mental disorders as unacceptable without their own consent. Most patients (73.1%) consider the control of medication in psychiatric hospitals to be a necessary measure.

Concerning compulsory feeding in case of patient’s refusal to eat, the vast majority of patients, 85.5% of males and 88.8% of females, consider it justified, since this is one of the fundamental human needs. Only 12.5% of the patients participating in the survey reported the inadmissibility of forced feeding under any circumstances.

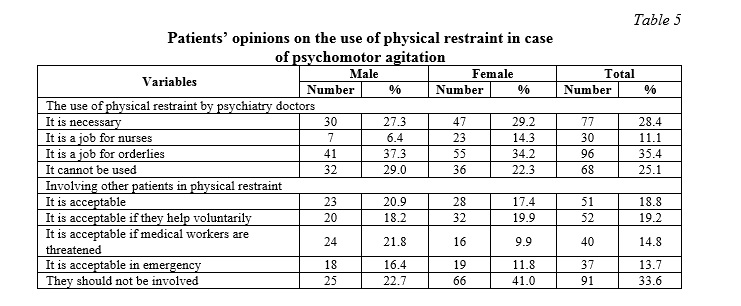

According to 35.4% of patients, the use of physical restraint (Table 5) in case of the danger of heteroaggression is the prerogative of the junior medical staff, and 28.4% believe that the psychiatrists themselves can use it. Also, the majority of patients, 61.8% of males and 66.5% of females, empower the psychiatrist to forcibly administer sedatives to patients in case of psychomotor agitation. Only a quarter (25.1%) of patients reported the inadmissibility of the use of fixation even in cases of aggression.

Concerning the practice of involving other patients to help with the implementation of physical restraint in cases of aggressive psychomotor agitation, women more often oppose to it (41%; c2=8.9752 p=0.004; OR=2.4 5% CI= 1.3-4.2) than men (22.7%). In general, 77.3% of male patients and 59.0% of female patients (c2= 8.9752 p=0.004) consider rendering assistance to medical workers acceptable in such cases. The males (21.8%) are more likely (c2=6.4177 p=0.012 OR=2.5 95%CI=1.2-5.3) than females (9.9%) to allow other patients to participate in keeping an aggressive patient who threaten the medical staff.

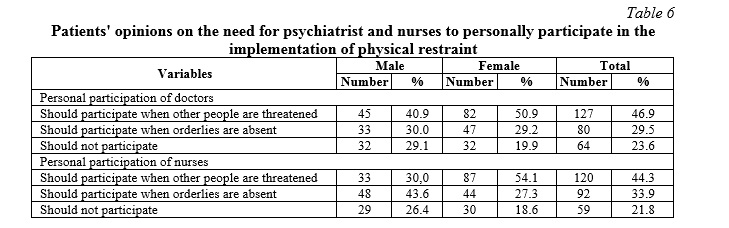

Most people with mental disorders undergoing inpatient treatment, 70.9% male and 80.1% female, believe that the psychiatrist should be directly involved in the use of physical restraint in the event of a life threat to others or in the absence of junior medical staff (Table 6).

The study found that many patients consider the use of physical restraint to be the responsibility of the medical orderly. However, they admit the possibility of their implementation independently by a psychiatrist in cases of threat to the lives of others or the absence of nearby medical staff, which is consistent with the results of other authors [25]. We have established gender differences: women are more likely than men to deny the possibility of involving other patients in retaining persons in a state of psychomotor agitation for the administration of drugs. However, in general, patients find this practice of assisting medical staff in cases of heteroaggression and destructive behavior acceptable. In most cases, patients delegate the forced administration of sedatives to a person in a state of agitation to psychiatrists. About 25% of patients in psychiatric hospitals are categorically against the use of physical restraint and coercion in any situation, which is confirmed by the results of other studies [26].

The results of our study differ from those previously obtained [27], where a negative attitude of patients towards compulsory drug intake was noted. Compulsory treatment of people with mental disorders, according to this study, is tolerated by most patients in order to ensure the safety of society and the well-being of the people with mental disorders themselves. This is due to the frequent refusal and evasion of patients from taking pills, leads to a decrease in the effectiveness of therapy and the risk of developing behavioral disorders. They consider it necessary to control the intake of medications by medical staff and force-feeding in case of refusal to eat.

Despite the high frequency of coercion and violence in the provision of psychiatric care in an inpatient therapy, only 16.6% of patients are in fact dissatisfied with the conditions of their stay. About a third of the patients in psychiatric wards (30.3%) rated the conditions and comfort of staying in a psychiatric clinic as high as 90-100 points out of 100. A study of the assessment of patient satisfaction with treatment in a psychiatric clinic showed that only 21.0% were not actually satisfied with the treatment, which is consistent with the data of Barnicot et al. [28], Woodward et al. [29]. A significant part, 38.0%, is indifferent to their treatment and the fact of being in hospital, and 41.0% of patients of both genders report that they are happy to be treated there. In the present study, more than 50.0% of patients were indifferent or dissatisfied with the organization of the treatment process itself, which, in our opinion, was due to insufficient criticism of their condition and characteristics of psychopathological symptoms.

Based on the studied attitude of patients towards coercion and violence in the provision of inpatient psychiatric care, we proposed recommendations for improving the conditions of their stay and treatment in a psychiatric hospital, including 3 areas: training of medical staff, organization of space and processes in the department, organization of patient care.

Recommendations regarding the competencies of medical staff: 1) inclusion of elements on legal aspects of psychiatric care, principles of bioethics in psychiatry using a contractual model of interaction [30], constructive professional communication with persons with mental disorders into programs of continuing medical education; 2) development at the state level of a normative legal act regulating the possibility of restricting the rights of persons with mental disorders, including the use of isolation and physical restraint measures; 3) development at the state level of unified clinical guidelines and protocols for the use of isolation and physical restraint measures in a psychiatric hospital; 4) development of protocols for informing psychiatric patients about medical intervention.

Recommendations concerning the organization of space and processes in the psychiatric ward: 1) development at the state level of uniform standards for organizing space, equipping wards and premises of psychiatric wards; 2) development at the state level of uniform standards for equipping isolation wards and observation rooms for patients to whom physical restraint is applied, using special restraining devices and installing video surveillance systems; 3) the implementation of household and communal processes by a specialized hospital service or the transfer of these processes to outsourcing.

Recommendations regarding the organization of patient care: 1) conducting psychoeducational trainings on an outpatient basis, including blocks on destigmatization, the formation of criticism of the condition, the skills of early recognition of exacerbations, the formation of compliance, increasing the level of responsibility for their health; 2) discussion of upcoming medical interventions, including physical restraint; 3) a discussion of the risks and consequences of avoiding medical intervention; 4) the use of psychosocial therapy and rehabilitation programs from the early stages of treatment in a psychiatric hospital.

Conclusions. The results of the study are important for studying the attitude of patients to treatment in a psychiatric hospital as one of the factors of compliance. The current negative opinion of patients about treatment in psychiatric hospitals requires more active development of the psychosocial therapy and rehabilitation system, the development of uniform standards for organizing comfort spaces and equipping wards and other rooms of psychiatric clinics, the development and implementation of trainings on the formation of a client-friendly approach for medical workers.

The use of restrictive measures in a psychiatric clinic requires the development of strict clinical and legal regulations, educational activities for the study of ethical and deontological aspects by medical staff of the psychiatric clinics, the development of psycho-educational trainings with patients and their relatives in psychiatric clinics.

Reference lists