Pathway directed mechanisms of anti-EGFR resistance in colorectal cancer (review)

Abstract

Background: Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) with cetuximab or panitumumab (anti-EGFR MAb) has been historically reserved for patients with RAS/BRAF wild-type advanced colorectal cancer (CRC). However, results of recent studies including PARADIGM and PRESSING evaluating the role of negative hyperselection of RAS wild-type CRC by alterations in other genes suggest that other genomic factors beyond RAS/BRAF/ERBB2 might influence the response to anti-EGFR MAbs in CRC. Although vast, current data on the predictive role of individual biomarkers to anti-EGFR MAb is often misunderstood. The aim of the study:In this review, in light of recent findings, we aimed to summarize existing data on the influence of various signaling pathways and their individual components along with nongenomic factors for the optimal patient selection for anti-EGFR MAbs. Materials and methods: To collect available information on possible mechanisms of resistance to anti-EGFR MAb in patients with colorectal cancer we searched PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov in May 2024. We also searched proceedings from the major oncology conferences ESMO, ASCO, and ASCO GI up to May 2024. We further scanned reference lists from eligible publications. Results: In this review we outline current knowledge on the mechanisms of resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs beyond traditional KRAS/NRAS/BRAF mutations in CRC. We focus on the alterations of genes involved in signaling pathways downstream of EGFR that can be detected by comprehensive tumor profiling in real-world clinical practice. Conclusion: Despite many mechanisms affecting various signaling pathways beyond the traditional KRAS/NRAS/BRAF mutations that are thought to be implicated in the resistance to anti-EGFR MAb in CRC, future efforts are needed to clarify their significance. Ongoing sequencing efforts will clarify the need for expanding the list of alterations routinely tested for the selection of candidates for anti-EGFR MAb

Keywords: colorectal cancer, epidermal growth factor receptor, anti-EGFR resistance, cetuximab, panitumumab, anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies

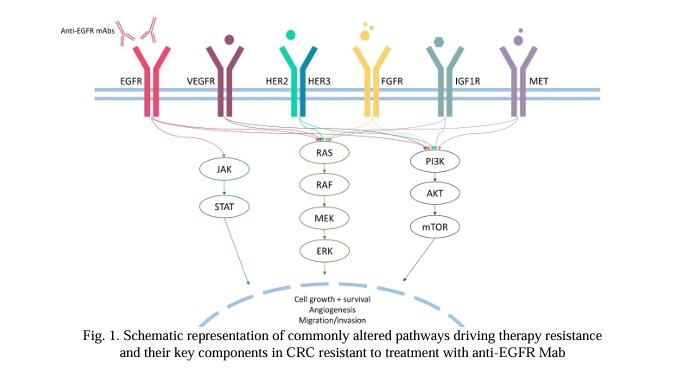

Introduction. Advanced colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer, and one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths [1]. Many molecular mechanisms of CRC progression have been described, including genes involved in Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK known as the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway as well as Wnt/β-catenin, transforming growth factor-β1/SMAD (TGF-β/SMAD) and Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAKs/STAT3) pathways [2]. Concomitantly genes regulating metabolism, as well as genes responsible for biotransformation of xenobiotics and antioxidant enzymes etc., affect the effectiveness of anti-EGFR MAb therapy, reducing it [3].

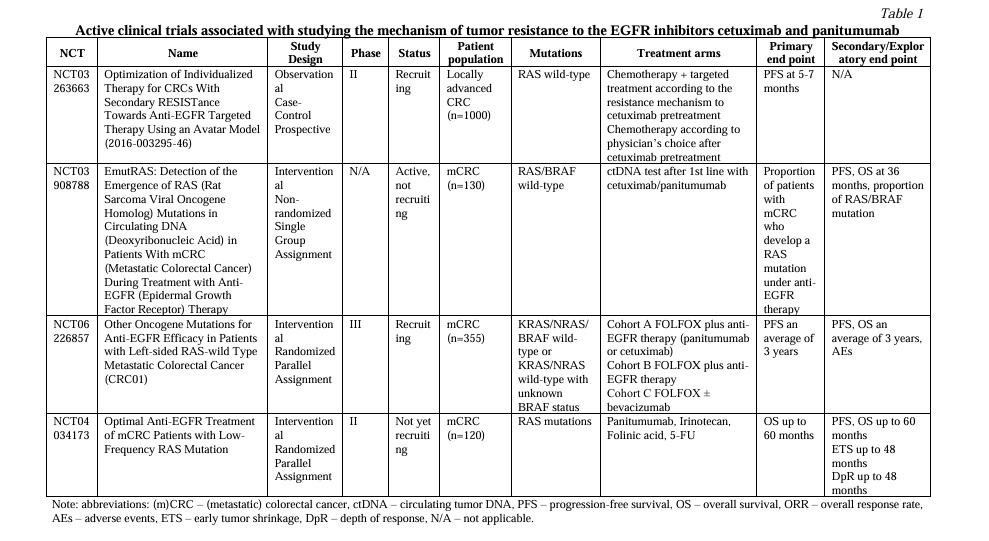

Development and approval of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies (MAb), cetuximab and panitumumab, have provided a significant survival benefit for patients with KRAS/NRAS (RAS) and BRAF wild type (wt) CRC [4]. However, while the development of acquired resistance to treatment is inevitable in most patients, some patients demonstrate intrinsic resistance [5-8]. In current clinical practice, treatment decisions regarding anti-EGFR MAbs are based on the analysis of classic biomarkers of resistance, such as mutations in RAS and BRAF genes [9, 10]. Various nonsystemic studies have previously reported on the influence of individual genomic alterations beyond RAS/RAF mutations on the benefit of anti-EGFR MAb therapy. However, the results of PRESSING and PARADIGM trials have truly reopened the question of the optimal selection of CRC patients for the anti-EGFR MAbs. Unlike previous studies, these studies suggest that the simultaneous screening of various genes frequently upregulated in CRC might be the most effective approach [11, 12]. However, current data suggests that not all of the alterations might be the same in terms of influencing the resistance to therapy. Therefore, it is important to address the impact of individual alterations in various genes, as the genes included in diagnostic panels used in real-world clinical practice might vary. In addition, several clinical trials are still ongoing (Table 1). In this review, we discuss current understanding of the mechanisms of resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs in CRC beyond RAS/BRAF V600 mutations. Here, we review mechanisms of both primary and acquired resistance with a focus on altered signaling pathways, and not on differentiation between the two.

1. Unconventional mechanisms of RAS/RAF-mediated resistance. The mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway, often known as the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway, is a highly conserved signal transduction pathway in all cells. The MAPK pathway is one of the best-characterized signaling cascades that regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, survival and apoptosis, by transmitting signals from upstream extracellular growth factors to various downstream effectors [13] (Fig.1). However, although widely investigated, there are still some unanswered questions regarding RAS/RAF-mediated resistance.

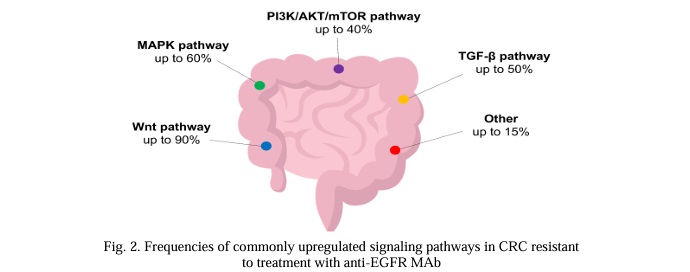

1.1 Unanswered questions regarding RAS. Oncogenic mutations in RAS are the most common molecular event in CRC (Fig.2). RAS mutations are detected in up to 60% of CRC patients; KRAS mutations are found in around 30% of cases, while NRAS mutations are found in about 5% of cases [14, 15]. Activating mutations are predominantly located in 2, 3 and 4 exons, affecting the catalytic G domain. The majority of observed mutations are substitutions that occur in hotspots affecting codons 12 (70-80% of all cases), 13 and 61 [16]. Rare activating missense variants affect codons 59, 117 and 146 [17]. Oncogenic activation of RAS genes is a known mechanism of resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs in CRC patients [18], as shown in numerous clinical studies [19-24]. RAS mutations are routinely analyzed by PCR, and the implementation of NGS analysis may increase the detection rate by 9% with tissue and X ctDNA analysis, respectively [25].

Although KRAS mutations are validated predictive biomarkers of resistance to cetuximab and panitumumab, patients harboring the KRAS G13D mutation might still derive benefit from cetuximab, as shown in several retrospective studies [26, 27]. This effect may be attributed to the atypical activating effect of the variant, as shown in functional studies [28]. A possible mechanism that distinguishes KRAS G13D from other activating variants was shown using a mathematical model and biochemical studies [29, 30]. According to the model, KRAS G13D is most likely sensitive to cetuximab due to a difference in the mechanism of interaction with NF1 and wt RAS. While other KRAS variants bind to wt RAS negative regulator NF1, effectively inhibiting the wt RAS inhibitor and leading to wt HRAS and NRAS activation, G13D does not interact with NF1, thus promoting NF1-mediated inhibition of wt RAS and the effective functioning of cetuximab. Thus, cetuximab treatment can block wt HRAS and NRAS activation. Although this hypothetical mechanism explains the atypical effect of the KRAS G13D variant, its clinical relevance remains unknown. Despite this evidence, a more recent retrospective analysis indicates that patients with KRAS G13D mutations are unlikely to respond to cetuximab [31]. However, both large retrospective and prospective trials failed to confirm this effect. Teipar et al. [27] reported a significant improvement of PFS (median, 7.4 vs 6.0 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.47; P = 0.039) and tumor response (40.5% v 22.0%; odds ratio, 3.38; P = 0.042), but not survival (median, 15.4 vs 14.7 months; HR, 0.89; P = 0.68) in those receiving cetuximab harboring KRAS codon 13 mutations. Similarly, in a retrospective analysis by Peeters et al. [32] the presence of KRAS G13D was significantly associated with a negative impact on OS (P = 0.0018). In a phase II Fleming single-stage design study by Schirripa et al. [33] evaluating the activity of single-agent cetuximab in KRAS G13D-mutated CRC, the primary objective of the trial was not met, DCR at 6 months was 0%.

Studies show that patients with low variant allele frequencies (VAF) of RAS/RAF might still be candidates for anti-EGFR therapy. In a post hoc analysis of the CRYSTAL study, it was shown that patients with RAS-mutated CRC whose mutations had low VAF in the tumor (0.1%-5%) benefited from the addition of cetuximab to FOLFIRI [34]. Similar results were obtained in a phase II ULTRA trial. Based on the results of this study, the optimal threshold for VAF of RAS/RAF mutations was established to be 5%. Across patients with RAS/BRAF mutation whose mutations had VAF of 5% and less, the response rate as well as median overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were similar to the RAS/BRAF wt patient cohort [35]. Noteworthy, this threshold is only used when tissue is analyzed and is not applicable for ctDNA analysis. When ctDNA is used, the tumor is considered RAS-mutant if the mutation is identified with any VAF.

Another member of the RAS oncogene family is HRAS. However, alterations in HRAS are rare in CRC [15], hence only anecdotal evidence points toward the association between HRAS mutations and resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs [36].

In the case of KRAS G12C-mutated CRC, another treatment strategy is the combination of specific KRAS G12C inhibitors (i.e. sotorasib, adagrasib) to anti-EGFR MAbs [37]. The combination treatment is preferable to KRAS G12C inhibitor monotherapy, as frequently observed mechanisms of acquired resistance to these drugs include new RTK pathway alterations, which can be targeted by EGFR inhibitors [38].

Finally, KRAS amplification is another alteration that can be found in CRC. KRAS amplifications are extremely rare among patients with CRC (<1%) and are usually mutually exclusive with other KRAS alterations [39]. KRAS amplification has been suggested to drive resistance to anti-EGFR treatment in a small patient cohort [18, 39, 40]. In vitro cetuximab could partially abrogate phosphorylation of MEK and ERK but, like in KRAS mutant cells, was unable to induce growth arrest in KRAS amplification-positive cells [18].

1.2 De novo RAS mutations and neoRAS. Another known mechanism of acquired resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs is the emergence of de novo RAS mutations in the course of treatment [18, 41, 42, 43]. The emergence of RAS mutant subclones can be detected months prior to the radiographic documentation of disease progression via liquid biopsy [18, 43]. At the same time, the discontinuation of anti-EGFR MAb might be associated with a decrease of the level of acquired RAS mutations [44]. Thus, assessment of acquired RAS mutations in liquid biopsies is necessary not only for the timely detection of acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors, but also for when considering therapy re-challenge [45, 46, 47].

An opposite phenomenon known as ‘neoRAS wild-type’ is characterized by the conversion of RAS-mutant tumors to RAS wt, as detected in ctDNA in the course of treatment with standard therapies. However, this phenomenon is thought to be uncommon, occurring in only 1-8% of patients [48]. One patient in the case series by Osumi et al. [49] with neoRAS has been reported to exhibit a long-term partial response (PR) to panitumumab in combination with irinotecan. Results of the SCRUM-Japan GOZILA study reported an incidence of neoRAS of 9%. In this study, out of 6 patients with neoRAS, 1 patient had PR and another had SD for at least 6 months [50].

1.3 Non-V600 BRAF mutations. Activating mutations in BRAF occur in 8-12% of patients with CRC, with the most common missense mutation BRAF V600E accounting for up to 95% of all BRAF mutations [51-54]. BRAF V600E is widely known to be one of the most common causes of primary resistance to EGFR therapy in CRC [55, 56]. BRAF V600E leads to constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway, and therefore inhibition of the MAPK pathway by EGFR inhibitors alone is not effective [57]. However, it has also been shown that monotherapy with BRAF inhibitors is also not effective in BRAFV600E CRC, which may be explained by EGFR-mediated feedback reactivation of MAPK signaling [58]. The addition of BRAF inhibitors in combination with EGFR inhibitors has been shown to restore the sensitivity of BRAF-mutant tumors [59-65]. A combination of encorafenib and cetuximab was approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with BRAF V600E CRC based on the results of the BEACON trial [62].

Class II and III BRAF variants can be seen in about 2.2% of CRC patients. BRAF non-V600 mutations mostly affect codons 594 and 596 [66, 67, 68]. Class II mutations are activating and signal in dimers in a RAS-independent manner. Class III BRAF mutations typically exhibit reduced kinase activity or absence thereof, however can still activate MAPK through signaling through increased RAS binding or CRAF activation, which is RAS-dependent [69].

The data on the effect of non-V600 BRAF mutations in terms of their influence on the efficacy of anti-EGFR therapy is conflicting [70]. Preclinical data as well as several case reports suggest that BRAF non-V600 mutations (specifically, class IIB and III mutations) may be sensitive to EGFR inhibition due to the dependency on upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling [51, 71].

However, clinical studies have suggested that BRAF non-V600 mutations might be implicated in the resistance to anti-EGFR MAb. In a retrospective study among 36 patients with BRAF class II and III mutations, the median survival of patients was significantly higher than for patients with BRAF V600E (36.1 months vs 21 months), however, among 11 patients receiving anti-EGFR therapy, no responses were observed, while 6 patients achieved stable disease as best response [72]. Similar results were obtained in another study, where among 4 CRC patients with non-V600 BRAF variants no one responded to cetuximab therapy [73]. Studies suggest that different non-V600 BRAF mutations might have a different effect on the efficacy of anti-EGFR MAb. In a study by Yaeger et al. [74] it has been suggested that response in CRCs with class II BRAF mutants is rare, while a large portion of CRCs with class III BRAF mutants might respond to therapy, based on the difference in objective response rate (ORR) in the two groups (8% vs 50%).

Differences in the effect of anti-EGFR MAbs on CRC with BRAF mutations of different classes may be attributed to differences in their biological properties. For instance, class III BRAF mutations are largely dependent on upstream EGFR signaling, and thus might be more sensitive to EGFR inhibition [71]. Additionally, non-V600 BRAF mutations in CRC are rare, and thus may be largely understudied.

1.4 Other mutations in MAPK pathway genes. Mutations in genes other than RAS/BRAF in the MAPK pathway may also be associated with resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs in CRC.

For example, gain of function mutations of MAP2K1 (encoding for MEK1) have been suggested as one of potential drivers of primary resistance but are not recommended for routine assessment due to insufficient validation in clinical trials [75]. MAP2K1 mutations, especially p.Lys57, were found in CRC patients with shorter PFS [76, 77] and were also recently found to be implicated in acquired resistance to anti-EGFR agents [39, 75, 78].

NF1, another gene involved in the MAPK pathway, encodes for a negative regulator of KRAS and plays a negative regulatory role in signaling downstream of EGFR due to its function as a RAS GTPase activating protein [79, 80]. It was demonstrated that NF1 loss might be one of the potential mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors in CRC [76, 81, 82]. NF1 inactivation has also been associated with decreased sensitivity of human lung cancer cells to EGFR inhibitors, which can be attributed to enhanced RAS signaling [83].

GTPase RAC1 and its alternatively spliced isoform RAC1B, important components of the pathobiology of various tumor progression processes, were shown to be involved in anti-EGFR MAb resistance using CRC cell lines [84], as well as surgical specimen from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients [85].

Mutations in ARID1A, the most frequently mutated subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex in cancer, have been reported to be associated with a transcriptional signature predicting reduced efficacy of anti-EGFR MAbs. This effect can be partially attributed to the activation of PI3K/MAPK signaling and loss of SWI/SNF activity [86]. However, further studies are warranted to confirm these findings.

2. PI3K pathway-mediated resistance. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR (PI3K) pathway is the second most commonly upregulated intracellular signaling pathway in CRC. In CRC, the oncogenic activation of the PI3K pathway frequently occurs through gain of function mutations of PIK3CA, as well as loss of function mutations, deletions or loss of expression of PTEN – all common events in CRC [87]. For instance, PIK3CA exon 20/PTEN/AKT1 alterations were found in 10.9% of older patients receiving panitumumab plus FOLFOX or 5-FU/LV [88]. The PI3K pathway is an important signaling pathway downstream of EGFR, exhibiting crosstalk with other signaling pathways, including MAPK [89, 90]. It has been proposed that the oncogenic activation of the PI3K pathway might play a role in generating resistance to EGFR-targeting therapies in CRC due to the activation of signaling downstream of EGFR [89, 91]. However, since dysregulation of the PI3K pathway often coexists with RAS/BRAF mutations, the individual roles of PI3K alterations in terms of anti-EGFR resistance warrants further investigation [87].

2.1 PIK3CA. Oncogenic mutations in PIK3CA occur in RAS-mutant and in RAS-wt CRC, suggesting that they might possess both driver and passenger roles depending on the molecular context [92, 93]. PIK3CA is altered in up to 20% of CRCs [87, 92] (Fig.2). In over 1.5% of tumors, double-hit mutations are observed, which are associated with increased PI3Kα signaling [94]. Activating mutations are predominantly located in exons 9 and 20 of the gene, affecting kinase and helical domains. However, recent studies suggest that less common activating mutations can occur in other exons of the gene [95, 96, 97].

Although molecular testing is routinely performed for patients with CRC, the data on the activity of anti-EGFR MAbs against PIK3CA-mutated tumors is limited. Although responses can be observed occasionally, PIK3CA mutations are generally associated with resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs, as shown by lower PFS and OS rates across patients with PIK3CA mutations [25, 91, 98, 99]. This effect appears to be especially pronounced in patients with exon 20 PIK3CA mutations, whereas exon 9 mutations do not seem to be predictive of response to anti-EGFR therapy [91, 99, 100]. This difference can be attributed to the domain-specific nature of activating properties of various PIK3CA mutations [101]. However, some studies report no effect of PIK3CA mutations on OS in RAS wt tumors [98, 102]. Although potentially significant, these findings should be interpreted with caution, since no randomized controlled trials have been carried out.

2.2 PTEN. When compared to PIK3CA, PTEN is less frequently altered in CRC (~5-7%) [87]. PTEN is a negative regulator of the PI3K pathway, and its loss or loss of function leads to aberrant PI3K signaling [103]. PTEN loss of function (LoF) mutations, as well as loss of protein expression due to promoter hypermethylation are associated with features of the sessile-serrated pathway [104, 105]. PTEN mutations/loss of expression have been associated with reduced response rates to cetuximab [106, 107]. Lack of response to panitumumab has also been reported across patients with PTEN loss or LoF mutations [107]. Additionally, reduced PTEN copy number has also been implicated in resistance [106, 107]. However, the number of studies that investigated the individual effect of PTEN alterations is small, warranting further validation.

2.3 Other components of the PI3K pathway. Although mutations affecting PIK3CA or PTEN are the most common in CRC, impact of alterations in other genes encoding for the components of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway has been reported. PIK3R1 encodes the p85α subunit of PI3K and acts as a regulator of the p110α catalytic product of the PIK3CA locus. Additionally, it has been proposed that PIK3R1, together with PIK3R2, is involved in the regulation of PTEN protein stability [108, 109]. Interestingly, PIK3R1 tends to be altered in RAS/BRAF wt tumors, albeit at low frequency [76]. In vitro studies have identified decrease of PIK3R1 expression as a potential mechanism of anti-EGFR resistance [110].

Point mutations in AKT1 occur at lower rates as compared to PIK3CA/PTEN alterations in CRC [86]. AKT1 oncogenic mutations, primarily E17K, had been identified in CRC patients initially resistant to anti-EGFR treatment [111, 112]. Additionally, AKT1 mutations are associated with concurrent RAS/BRAF mutations [111].

The impact of FBXW7 alterations on the resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs remains controversial. The F-box protein FBXW7 is also implicated in the PI3K signaling [113]. Alterations of FBXW7 have been identified in CRC patients displaying short PFS and lack of response to anti-EGFR treatment, however the small sample size and the retrospective nature of data do not allow to draw univocal conclusions [76, 114, 115].

Combinations of anti-EGFR MAbs with various targeted agents, such as mTOR inhibitors, have also resulted in high efficacy, warranting further validation in larger patient cohorts [116, 117, 118]. However, clinical evaluation of an experimental PI3K inhibitor combined with cetuximab for KRAS wt CRC patients unselected for the alterations of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, had limited activity [119].

3. RTK. Mutations in receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) lead to the autophosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase domain resulting in conformation changes and activation of downstream signaling pathways. Alterations of different RTKs can be found in CRC, the majority of which have the potential to activate PI3K and MAPK signaling [120], highlighting that the oncogene addiction can be a driver of anti-EGFR therapy resistance.

3.1 HER/ERBB family. Amplifications of ERBB2 occur in up to 3% of tumors, and outline a distinct patient population [87]. RAS/BRAF/PIK3CA quadruple wild-type tumors are especially enriched for ERBB2 amplifications, which are observed in up to 20-30% of cases [121]. ERBB2 amplifications have long been recognized as a mechanism of primary resistance to anti-EGFR mAbs, as they have been shown to be associated with worse PFS and ORR in various studies [122, 123]. However, the question of what threshold of ERBB2 amplification should be taken into account when considering EGFR MAb requires further studies [124].

In a similar manner to ERBB2 amplifications, ERBB2 mutations result in downstream pathway activation, and thus have the potential to mediate resistance to EGFR-targeting agents [125]. Consistently, various studies have validated the association between ERBB2 mutations, particularly the ones occurring in the tyrosine kinase of the protein, and resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Interestingly, ERBB2 mutations can be attributed to both primary and acquired resistance [126]. In the era of NGS, these findings have become more relevant than ever before due to the potential of NGS to identify not only ERBB2 amplifications, but also mutations.

Preclinical studies suggest that ERBB3 mutations may also influence the effectiveness of EGFR MAb in CRC, as well as in HNSCC. This effect can be explained by the activation of the PI3K pathway caused by ERBB3 oncogenic mutations [127]. However, in a retrospective study by Loree et al. ERBB3 mutations exhibited a less pronounced effect on the effects of EGFR MAb treatment when compared to ERBB2 mutations [128].

For cancers with sustained ERBB signaling, the addition of ERBB TKIs has been investigated, resulting in promising antitumor activity [129, 130, 131]. Despite the promising activity of other agents, when combined with cetuximab or panitumumab, pan-ERBB TKI neratinib failed to produce any objective responses among patients with RAS/BRAF/PIK3CA wt CRC [132].

3.2 EGFR ECD mutations. In some cases, acquired resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs can be mediated by the emergence of EGFR ectodomain (ECD) point mutations [133]. EGFR ECD mutations may arise in up to 16% of patients treated with EGFR MAbs [133]. Several EGFR ECD mutations have been reported, including, among others, R451C, S492R, G465R, K467T [134-138]. Contrary to activating mutations of the EGFR, most of the EGFR ECD mutations lie in the surface recognized by EGFR MAbs and have the potential to affect complex formation. Some mutations (i.e. R451C) that are not specifically located in EGFR MAb binding sites introduce other critical structural changes [134]. Importantly, a subset of these mutations (such as S492R) may only affect the interaction with cetuximab and not panitumumab [133, 134], which may be attributed to the presence of a large central cavity in panitumumab but not cetuximab [139].

Switching from cetuximab to panitumumab has been reported to be an effective strategy for treating cetuximab-resistant CRC patients with acquired EGFR ECD mutations, as a significant subset of these mutations does not prevent panitumumab binding [134]. Moreover, Sym004, a 1:1 mixture of cetuximab and panitumumab has been shown to be an effective treatment strategy for EGFR ECD-mutated CRC in vitro [140]. Therefore, for CRC patients with EGFR ECD mutations no additional agents might be needed apart from standard EGFR MAb.

3.3 MET amplification. Alterations of the MET are a well-established mechanism of resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [141, 142]. Similarly to NSCLC, MET amplifications, albeit occurring at lower frequencies (around 1%), have been found to drive resistance to anti-EGFR mAb in CRC. Using patient-derived tumor xenografts, Badrelli et al. showed that MET amplification might be associated both with primary and acquired resistance in KRAS wt CRC, which was then supported by patient cases [143]. This effect can be attributed by the activation of the downstream PI3K and MAPK induced by MET [144].

In MET-amplified CRC, a combination of MET and EGFR targeting agents have resulted in the improvement of patients’ outcomes, although the data on the combination of these drugs are limited [145].

3.4 Kinase fusions. Kinase fusions are rare in CRC, occurring in less than 1% of the patients [87, 146]. However, kinase gene fusions are estimated to be enriched in RAS/BRAF wt tumors in patients that will be potentially treated with EGFR MAbs [147], or mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite unstable (dMMR/MSI) tumors [148, 149]. Specifically, ALK, BRAF, NTRK, RET gene fusions have been reported in patients with CRC [88, 112, 147, 150]. Kinase gene fusions have been identified in EGFR MAb treatment resistant CRC patients [112], however, their effect has been underexplored in large randomized studies due to low prevalence. Additionally, kinase fusions have been found to be enriched in dMMR/MSI colorectal cancer, which can further explain resistance [151].

3.6 Other. Other uncommon RTK-mediated mechanisms of resistance have been suggested. For instance, although rare in CRC, in vitro studies have identified FGFR1 amplifications as mediating resistance to anti-EGFR mAbs, possibly due to the activation of compensatory pathways, however, these findings have not been further investigated to date [143].

Upon binding with growth factors and insulin, the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) activates the two most commonly upregulated signaling pathways in CRC, the PI3K and MAPK [152]. Elevated expression of IGF1R has been found to be a poor prognostic factor in CRC [153]. Low IGF1R expression has been found to correlate with better outcomes with cetuximab treatment [154]. However, the data regarding the effect of IGF1R expression on the efficacy of EGFR-targeting therapy is inconsistent [154, 155].

Persistent activation of the JAK/STAT pathway has also been linked to anti-EGFR therapy. Specifically, activation of STAT3 through phosphorylation correlated with the resistance to EGFR TKI gefitinib in CRC cell lines, suggesting that STAT3 phosphorylation may play a role in mediating resistance to EGFR inhibitors in CRC [156].

VEGF and EGFR signaling pathways are closely related, sharing multiple downstream effectors. VEGF signaling plays a crucial role in angiogenesis, and inhibition of angiogenesis is one of the mechanisms of action of anti-EGFR MAb. Increased expression of VEGF has been reported to be associated with decreased response to cetuximab [157]. Dual targeting of VEGF and EGFR represents a promising strategy for overcoming resistance mediated by either VEGF, or VEGF/EGFR crosstalk [158, 159].

5. Wnt signaling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. The Wnt pathway is commonly divided into β-catenin dependent, or canonical, and independent, or non-canonical, signaling pathways [160]. The canonical Wnt signaling pathway plays one of the most important roles in CRC carcinogenesis [161]. Wnt activation in CRC occurs through inactivation of APC approximately in 50% of cases, or through mutation of β-catenin [160]. Wnt signaling pathway promotes the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, which contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and increased tumor aggressiveness [162]. In CRC cell cultures, it was shown that the expression of E-cadherin, a marker of epithelial cells, may be associated with the effectiveness of EGFR inhibition. At the same time, mesenchymal cells were 7 times less sensitive to anti-EGFR MAbs when compared to epithelial cells [163]. These findings were also validated in other tumor types. For instance, in treatment-naive patients with HNSCC who received cetuximab before surgery, upregulation of expression of genes implicated in CAF and EMT including markers of embryologic pathways like NOTCH and Wnt was demonstrated [164]. There is also supporting preclinical data for other cancer types besides CRC [165-168].

While some studies suggest that APC mutations might contribute to anti-EGFR MAb resistance, the data is inconsistent. For instance, Thota et al. reported that APC mutations in the context of TP53 mutations may, in fact, predict cetuximab sensitivity [169].

6. TP53. Alterations in TP53, commonly referred to as ‘guardian of the genome’ can be found in the vast majority of CRC cases (>70%) [87]. Several studies have reported that TP53 wild-type or TP53-expressing CRC tumors exhibit worse outcomes when treated with anti-EGFR MAbs when compared to TP53-mutant tumors, however other factors, such as tumor sidedness, might contribute to this effect [170-173]. In vitro studies suggest that EGFR expression can be differently modulated depending on the TP53 mutational status, and TP53-mutant status is generally associated with increased EGFR expression, which can explain the differences in anti-EGFR MAb sensitivity [174, 175].

7. TGF-β pathway. The transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway is involved in many biologic cellular processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and extracellular matrix production [176]. In the early CRC carcinogenesis, activation of TGF-β leads to tumor suppression [177]. However, in advanced stages, TGF-β is believed to promote metastasis, angiogenesis, and EMT [178, 179].

SMAD4 is a common mediator in the transcriptional regulator complex in the TGF-β pathway [180]. It has been demonstrated that SMAD4 mutations can lead to cetuximab resistance in CRC patients. The modified PFS (mPFS) and ORR to cetuximab has been reported to be decreased for SMAD4-mutated patients when compared to SMAD4 wt patients [81, 115]. Similar results have also been shown in other studies [181] and for other tumor types, specifically for HNSCC [182, 183].

8. Non-genomic mechanisms of resistance. Various other non-genomic mechanisms driving EGFR MAb resistance have been proposed. For instance, dMMR, caused by a dysfunction of mismatch repair and occurring in up to 15% of CRC patients, has been reported to play an important role in mediating resistance [184]. Although the mechanism underlying resistance in dMMR/MSI CRC cases remains largely unknown, it has been shown that in cases where dMMR/MSI is caused by the hypermethylation of MLH1 promoter (commonly referred to as sporadic dMMR/MSI) increase in the expression of ERBB2, as well as PI3K signaling can be observed [185]. However, in this case, the increase in the ERBB2 expression might not be clinically significant, as ERBB2 amplification-positivity and MSI are mutually exclusive in CRC [186]. Additionally, sporadic dMMR/MSI is commonly associated with BRAF V600E mutations, whereas mutations in other oncogenes known to drive resistance to anti-EGFR MAb are frequently found in Lynch syndrome-associated CRC [187].

Apart from dMMR/MSI, the immune microenvironment by itself can be considered as an important modulator of anti-EGFR MAb efficacy. Specifically, increase in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), which produce mitogenic growth factors such as FGF1, FGF2, HGF, TGF-β and others, as well as angiogenesis and abnormal functioning of various immune cells have been demonstrated to modulate resistance [82].

Additionally, metabolic reprogramming, which can occur following treatment with EGFR-targeting agents, can influence therapy efficacy [188]. Autophagy, a self-cannibalization biological process, is another factor that should be considered when discussing mechanisms of resistance to EGFR-targeting agents. It has also been proposed that autophagy acts as a protective response in cancer cells [189]. Finally, cancer stem cells, also known as tumor-initiating cells, have also been suggested to play a part in drug resistance, due to their ability to self-renew and differentiate into various cell lineages [190].

Furthermore, gut microbiota composition has been found to modulate therapy efficacy in various tumors, including CRC. However, data regarding the effect of gut microbiota on the efficacy of anti-EGFR MAbs is currently limited. A small study by Lewandowski et al. [191] found that patients with high diversity of gut microbiome may be better candidates for anti-EGFR MAb therapy, as compared to patients with non-diverse microbiome. However, these findings should be further validated, as diverse gut microbiomes have been linked to a good prognosis of CRC patients regardless of therapy [192].

Finally, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, and circular RNAs have been reported to regulate resistance to anti-EGFR MAb in CRC. One of the suggested mechanisms explaining this phenomenon is that different ncRNAs can upregulate oncogenic signaling pathways promoting resistance to anti-EGFR therapy [193].

Discussion and conclusions. Monoclonal antibodies that target EGFR blocking downstream signaling have emerged as important therapeutic agents in the treatment of CRC. The indication of drugs from this class, cetuximab and panitumumab, is currently based on the mutational statuses of KRAS, NRAS and BRAF genes [9, 10]. Until recently, the question of whether additional factors play a role in resistance to anti-EGFR MAb has not been widely investigated. However, the encouraging results of trials evaluating the role of the hyperselection have reopened the question of the optimal selection of CRC patients for the anti-EGFR MAbs once again [11, 12].

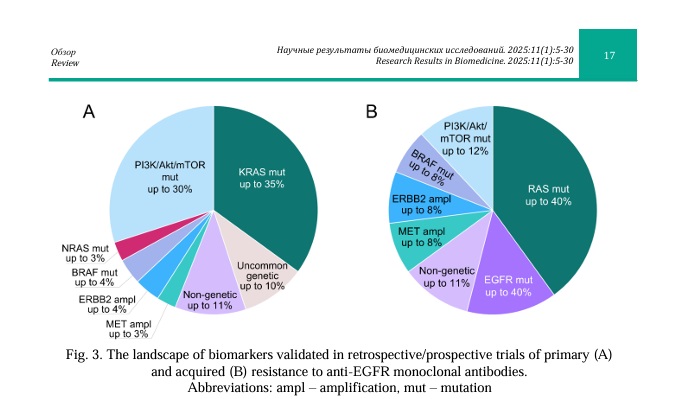

Here, we outline current knowledge on the mechanisms of resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs beyond traditional alterations in CRC. Specifically, we focus on the alterations of various genes involved in relevant signaling pathways downstream of EGFR that can be detected by genomic assays currently used in the real-world clinical practice. Despite the fact that some of the discussed biomarkers have been extensively studied, their individual use in the clinic is limited by the lack of randomized clinical studies. Therefore, it will be necessary to validate the clinical utility of these alterations in large cohort studies for optimal patient management. Future efforts should be directed at optimizing strategies to overcome resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs in patients with various genomic alterations. The most common mechanisms of intrinsic and acquired resistance are summarized in Figure 3.

Many attempts have been made towards the development of strategies to overcome resistance to anti-EGFR MAb in CRC [194]. Combining anti-EGFR MAbs with targeted agents represents a promising strategy for overcoming treatment resistance arising from compensatory pathway activation, although further studies are warranted to improve patient outcomes. Additionally, novel agents may be used as standalone therapies for patients with various alterations, such as aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling, for instance [195, 196].

Apart from genetically-driven resistance, growing evidence suggests that various non-genetic mechanisms might be implicated in the resistance to anti-EGFR MAbs in CRC. Although currently these findings are mostly of academic interest, with the advances of novel assays, it will be possible to incorporate their analysis into routine clinical practice.

In current clinical practice, tumor sidedness plays a crucial role in clinical decision making, which is largely driven by differences in their biology. For instance, right-sided tumors are more likely to have MSI, as well as display higher rates of oncogenic EGFR activation, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations, which factor into therapy resistance [197]. However, further efforts should be directed towards the implementation of comprehensive genomic testing into routine clinical practice, which will allow to focus on genomic portraits of tumors, and not only their sidedness.

In conclusion, while many mechanisms affecting various signaling pathways beyond the traditional RAS/BRAF mutations are thought to be implicated in the resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer, future efforts are needed to clarify their significance. Ongoing sequencing efforts will clarify the need for expanding the list of alterations routinely tested for the selection of candidates for anti-EGFR therapy.

Financial support

This study was supported by a grant from theMoscow Center of Innovative Technologies in Healthcare (№2102-2/23).

Reference lists